This is the fourth post in a series exploring how we got our beliefs. Each month, we journey to a pivotal moment in Christian history: the councils that forged our creeds, the splits that shaped our traditions, the debates that still echo in today’s churches. We’re not just learning dates and names; we’re discovering why Christians think and worship as we do, and what these ancient conflicts teach us about contemporary divisions.

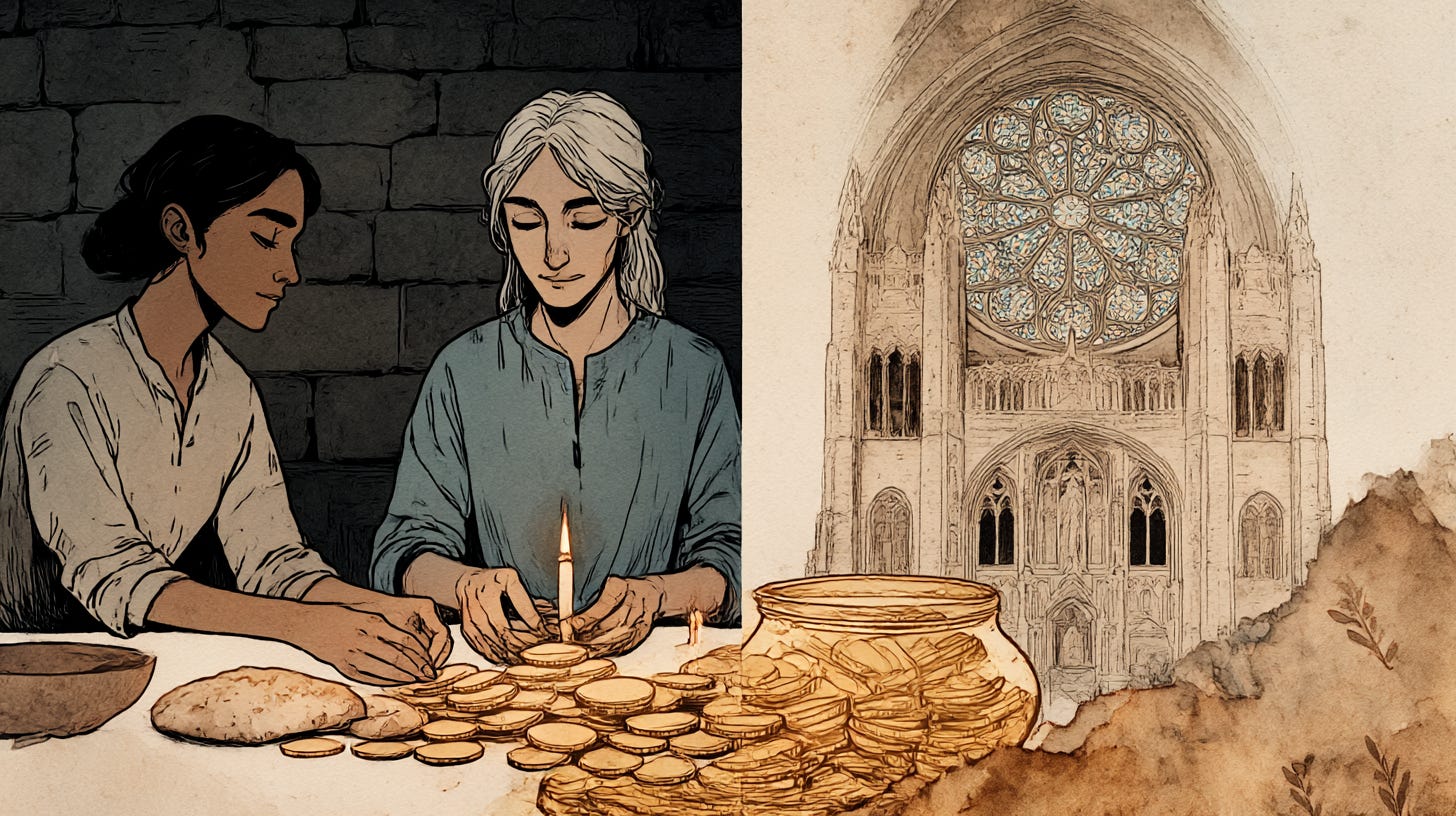

I sat in the church sanctuary after a finance committee meeting in my last parish. We’d just reviewed our property portfolio: a Victorian church building (£5 million), a four-bedroom vicarage, a crypt church hall, and investments (another two million). Not bad for 80 Sunday attenders.

Then I read Acts 2 for evening prayer:

“All who believed were together and had all things in common; they would sell their possessions and goods and distribute the proceeds to all, as any had need.”

The contrast startled me. The early church shared everything. My church owns everything. What happened?

I’m not asking whether the first Christians were communists—wrong question for a different era and, frankly, naive. I’m asking something more complicated: Did we lose something essential when we stopped sharing, or mature into something better?

The answer involves persecution, imperial favour, and monks who tried to recover what was lost.

The Jerusalem Experiment

The book of Acts describes something extraordinary. The first Christians in Jerusalem didn’t just attend services together—they pooled their resources. “No one claimed private ownership of any possessions, but everything they owned was held in common” (Acts 4:32). When people had needs, believers sold property to meet them. The wealthy Barnabas sold a field and laid the money at the apostles’ feet (Acts 4:36-37).

This wasn’t economic theory. It was an eschatological conviction—belief that Jesus was returning soon, possibly next week, certainly within their lifetimes. Why hoard property when the kingdom was breaking in? Pentecost had created family-like bonds that transcended normal economic relationships. They were “one heart and soul” (Acts 4:32), which meant sharing came naturally.

The theological basis ran deep. Jesus had taught, “Sell your possessions and give alms” (Luke 12:33). The Jerusalem community was simply doing what he’d said. They drew on Jewish traditions of economic justice—the Jubilee’s property redistribution, the Temple’s care for widows and orphans. And Greek friendship ideals claimed that “friends hold all in common.” The early church was creating something new from these elements.

But was it mandatory? When Ananias and Sapphira died for lying about property they’d sold, some concluded that property sharing was required (Acts 5:1-11). Yet Peter’s words to Ananias suggest otherwise: “While it remained unsold, did it not remain your own? And after it was sold, were not the proceeds at your disposal?” (Acts 5:4). They sinned by lying, not by keeping property. As historian Justo González writes, “This was not a law, but rather the joyful response of those who had experienced the new life in Christ.”

Voluntary, then. But expected. Total transparency required. You didn’t have to share everything, but you couldn’t pretend you’d shared when you hadn’t.

The system didn’t last long. Within a few years, the Jerusalem church was so poor that it needed relief from Antioch during a famine (Acts 11:27-30). A couple of decades later, Paul was still collecting money for “the poor among the saints at Jerusalem” (Romans 15:26). Either the economic model couldn’t sustain itself, or persecution scattered the community before it could mature.

But briefly, Christians actually lived Acts 2. Then they stopped. Why?

From Margins to Mainstream

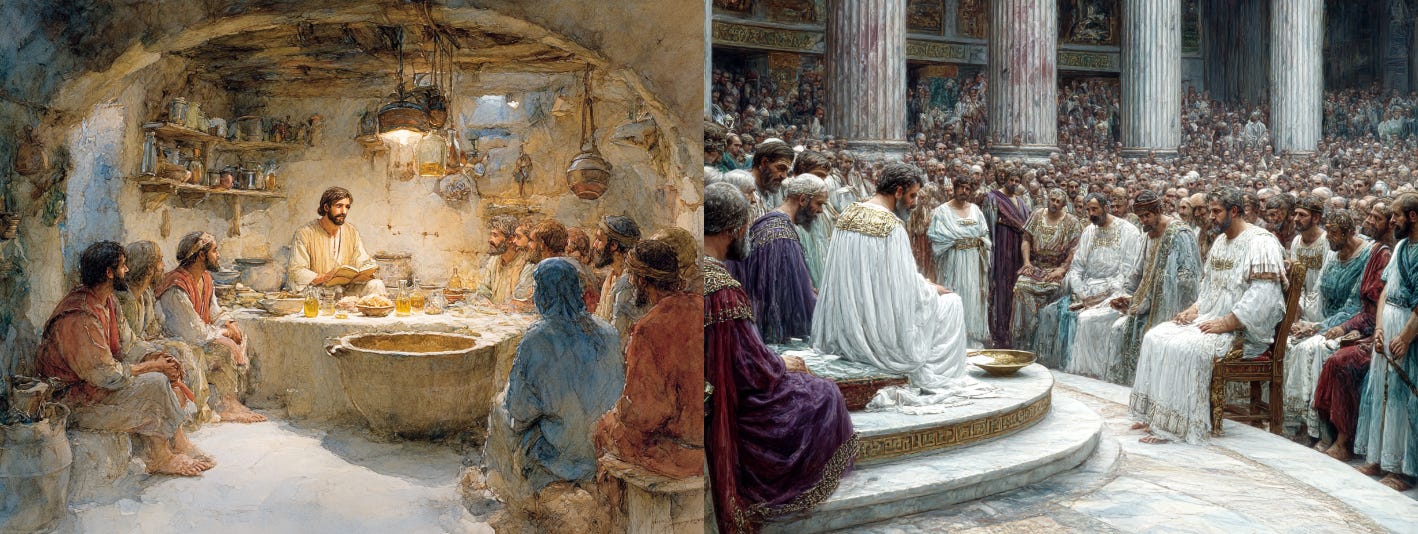

We don’t know precisely what ended the Jerusalem experiment. What we do know is how the next generations adapted the vision whilst facing different circumstances.

The post-apostolic church—the generation after the apostles—kept the ideal alive whilst adapting the practice. The Didache, a Christian manual written in the late first or early second century, instructed: “Share everything with your brother. Do not say, ‘It is private property.’ If you share what is everlasting, you should be that much more willing to share things which do not last.”

Christians owned property. But they shared generously. Justin Martyr, writing a generation after the apostles, described Sunday gatherings where collections supported “widows, orphans, those in bonds, strangers sojourning among us—in a word, all who are in need.” Tertullian reported around 200 CE that Christians maintained a common fund through voluntary monthly donations, supporting the burial of the poor, the care of orphans, and the ransom of prisoners.

This was mutual aid, not full communalism. But it was substantial. When plagues struck Roman cities in the third century, Christians cared for the sick—including pagans—whilst wealthier Romans fled. Sociologist Rodney Stark argues this practical love was the early church’s most powerful evangelistic tool.

Persecution made property accumulation impossible anyway. When emperors confiscated Christian property during waves of persecution, you couldn’t own much. The underground church depended on mutual aid because marginalisation demanded it.

Then Constantine changed everything.

The Edict of Milan in 313 CE granted religious tolerance and restored confiscated property. But Constantine didn’t stop there. He launched a lavish church-building programme, exempted clergy from taxes, appointed bishops to governmental roles, and donated land, money, and grain to churches across the empire.

Within a generation, the church transformed from an illegal sect to an imperial institution. Constantine built St Peter’s Basilica in Rome, the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem, and dozens of other churches. Historian Peter Brown writes in Through the Eye of a Needle: “The church moved from persecuted minority to favoured recipient of imperial patronage.”

Churches that had met in houses now owned basilicas. Bishops who’d been hunted criminals now controlled estates. Clergy who’d been supported by offerings now received salaries. Episcopal estates—land owned by bishops—developed to fund charitable work on a massive scale. The church had resources for hospitals, orphanages, and schools. But it also had wealth. Serious wealth.

The eschatological urgency—the sense that Jesus’s return was imminent—faded as well. The church settled in for the long haul between Pentecost and the Parousia (Christ’s second coming). This meant thinking differently about property. What had been temporary stewardship became potentially permanent holding.

Eusebius of Caesarea, in his Life of Constantine, developed a theology to match the new reality. Constantine’s favour was providential, he argued. God was blessing the church with resources to transform society. The visible, glorious institution wasn’t corruption—it was God’s plan all along.

But was it? The church lost the economic radicalism that marked it as different, the countercultural witness that came through generosity, and the urgency of expecting Jesus’s soon return.

What did it gain? Resources for ministry at scale. Institutional stability for long-term mission. The capacity to build hospitals and preserve manuscripts and educate thousands.

Did this corrupt or mature the church? The question haunted some fourth-century Christians enough that they headed for the desert to find out.

The Monastic Protest

Anthony of Egypt was about twenty when he heard Jesus’s words to the rich young ruler read in church: “If you wish to be perfect, go, sell your possessions, and give the money to the poor” (Matthew 19:21). Around 270 CE, he did precisely that. He gave away his inheritance, placed his sister in a community of virgins, and retreated to the Egyptian desert to pray.

He wasn’t fleeing the world. He was seeking the radical discipleship that seemed unavailable in the Constantinian church. Athanasius’s Life of Anthony records that “he went forth... having given away his possessions.” The desert fathers and mothers were reclaiming Acts 2 economics in smaller communities where it might actually work.

Pachomius organised this impulse into cenobitic monasticism—“cenobitic” meaning “common life,” with monks living in community rather than alone. Around 320 CE, his monasteries practised strict property rules: monks owned nothing individually, but everything was held communally. They supported themselves through agriculture and crafts, practised hospitality to travellers, and gave alms to the poor from their surplus.

Benedict of Nursia’s Rule, written around 530 CE, became the standard in the West. Chapter 33 asks, “On Whether Monks Should Own Anything,” and answers with absolute prohibition: “Above all, this vice must be uprooted and removed from the monastery. No one may presume to give or receive anything without the abbot’s leave, or to have anything as his own.” Chapter 34 addresses distribution: needs-based rather than equal shares. “Let all things be common to all, as it is written, so that no one presumes to call anything his own” (Acts 4:32).

The pattern is instructive. Monasteries renouncing wealth often became wealthy. Their discipline, agricultural innovation, and manuscript preservation made them economic powerhouses. The communities that fled property accumulation ended up accumulating impressive property.

But monasticism preserved something crucial: a living witness that Acts 2 was still possible. Monks embodied voluntary poverty as a protest against church wealth. Their economic sharing was a spiritual practice, a daily enacted reminder that the gospel demands something radical.

Peter Brown calls monasticism “the antithesis of the Christian empire.” Whilst bishops became landowners and churches accumulated estates, monks insisted that Jesus meant what he said about selling possessions and giving to the poor.

Yet monasticism also created a two-tier Christianity. Monks practised radical economics. Laity practised conventional property ownership. The compromise was comfortable: admire monastic poverty whilst maintaining your own wealth. Support the monastery financially, feel virtuous about their sacrifice, then go home to your estate.

The cycle repeated. Francis of Assisi founded the mendicants—begging orders who owned nothing—in the thirteenth century, renewing the poverty emphasis in reaction against monastic wealth accumulation. Within generations, they too had to reform splinter groups trying to recover Francis’s original vision.

The pattern suggests ongoing tension between gospel economics and institutional sustainability. Every radical movement eventually institutionalises. Every institution eventually needs a new radical movement to call it back.

The question remains: Should all Christians live like Acts 2, or only the specially called?

What This History Teaches Us

I’ve been thinking about what Oscar Cullmann called the “already/not yet” tension. The kingdom has come in Jesus. The kingdom is still coming at Jesus’s return. We live in between.

Acts 2 economics made sense when the “not yet” felt very near. When Jesus’s return seemed imminent, property ownership felt absurd, but as the church settled into the “already”—the long haul between Pentecost and Christ’s return—economic practices adapted.

Was this an inevitable compromise or a faithless accommodation? I honestly don’t know.

The early church fathers saw Acts 2 as a hoped-for ideal, even if not a mandatory requirement. Monasticism suggests it remains viable for those specially called.

Catholic social teaching developed a sophisticated framework for this tension. The principle of the “universal destination of goods”—that God intends earth’s resources for all humanity—grounds property rights in responsibilities toward the common good. You can own property, but it must serve more than private interest.

Protestant Reformers like Calvin emphasised vocation: God calls people to different economic roles, all serving neighbours through honest work. Your station in life matters less than your faithfulness within it.

(We explored the church’s nature in Pilgrim’s Essentials #8; here we’re tracing how that nature shaped economic practice.)

Neither Catholic nor Protestant tradition requires Acts 2 communalism for all Christians. Both insist property ownership carries obligations toward those in need. The question isn’t whether you own property but how you steward it for kingdom purposes.

Here’s the tension: Constantine’s church gained resources for large-scale charity. Building hospitals requires institutional property. Running orphanages, preserving manuscripts, and educating thousands—all require wealth. The effectiveness argument has force.

But Jesus didn’t promise effectiveness. He promised faithfulness. And the church’s institutional wealth sometimes corrupts our witness. When we look wealthier than we look generous, when our property portfolios impress more than our charity, when others do mutual aid better than Christians, we’ve lost something.

Ron Sider asks the uncomfortable question: “If early Christians genuinely had all things in common, what does that say about our way of doing church today?”

Some modern communities attempt Acts 2 economics. The Bruderhof, the Catholic Worker movement, and various new monastic communities practise property sharing and radical hospitality. They prove it’s still possible. They also prove it’s still costly, complex, and countercultural.

Most of us aren’t called to sell everything. But Acts 2 won’t let us rest easy with conventional property ownership either. The text keeps asking: How much is enough? What does generous sharing look like in your context? Do your economic practices reflect hope in Jesus’s coming or a worldly security-seeking mindset?

So What Do We Do?

I’m still standing in that church car park, metaphorically. I still don’t have easy answers about church property portfolios. But I’ve learned some questions worth asking.

For church leaders: Audit your property and investments. Ask whether these resources serve mission effectively or just feel comfortable. Consider what Acts 2 sharing might look like in your context. Not necessarily selling everything, but examining everything. Could you shift from accumulation to kingdom investment?

For individual Christians: Acts 2 may not require renunciation of property, but it demands an examination of generosity. What percentage of income and assets do you share? Do your financial practices reflect hope in Christ’s return or worldly security? Could you join or create an intentional community practising economic sharing?

For seekers: Early Christian economic radicality was an evangelistic force. Pagans noticed and said, “See how they love one another.” Modern church wealth sometimes repels rather than attracts. What would Christian witness look like if we recovered this edge?

I’m not romanticising the early church. They faced famine, persecution, and limited resources. But they had something we’ve lost: an economic practice that witnessed to the kingdom’s priorities. They took seriously that you cannot serve God and wealth.

Constantine’s favour gave the church buildings, budgets and bishops in Parliament. Whether that was a blessing or a curse, I’m still working out. But I know this: we need the monastic protest. We need communities choosing voluntary poverty. We need the awkward question Acts 2 keeps asking.

Because the church that owns everything, whilst the world starves, has forgotten something essential. And the church that shares remembers who we’re supposed to be.

Questions for Fellow Pilgrims

When you read Acts 2:44-45, do you see a prescriptive command or a descriptive snapshot? What determines your answer?

How do you reconcile property ownership with Jesus’s call to “sell your possessions and give alms”? Where’s the line between stewardship and hoarding?

Was Constantine’s favour a blessing or a curse for the church? Did the resources gained justify the loss of witness?

Have you experienced a Christian community practising economic sharing? What did it teach you about discipleship?

If urgency about Jesus’s return drove early church economics, what drives ours? Security? Comfort? Something better?

If five families from your church wanted to experiment with Acts 2-style sharing, what would that look like? What excites or scares you about that prospect?

Going Deeper

Essential Reading:

Luke Timothy Johnson, Sharing Possessions: What Faith Demands (2011) - best theological treatment

Justo González, Faith and Wealth: A History of Early Christian Ideas on Money (1990) - comprehensive historical survey

Peter Brown, Through the Eye of a Needle: Wealth, the Fall of Rome, and the Making of Christianity (2012) - magisterial study

Primary Sources:

Acts 2:42-47; 4:32-37; 5:1-11 - biblical foundation

Didache 4:5-8, in Bart Ehrman, The Apostolic Fathers (Loeb Classical Library) - early second century on property sharing

Justin Martyr, First Apology 67 - description of weekly collection

Benedict, Rule, Chapters 33-34 - monastic property rules

Contemporary Perspectives:

Ron Sider, Rich Christians in an Age of Hunger (6th ed., 2015)

Shane Claiborne, The Irresistible Revolution (2006) - new monasticism

Pope Francis, Laudato Si’ (2015), paragraphs 93-95 - contemporary Catholic social teaching on property

Rodney Stark, The Rise of Christianity (1996) - chapter on early Christian charity

Historical Context:

Peter Brown, Poverty and Leadership in the Later Roman Empire (2002)

Helen Rhee, Loving the Poor, Saving the Rich (2012) - patristic economic ethics.