This article is part of the Sign Posts series, which explores where 2,000-year-old faith meets 21st-century challenges—from artificial intelligence to mental health, from science-faith tensions to interfaith dialogue, helping fellow pilgrims navigate the intersection of ancient beliefs and modern realities. Read more Signposts here.

An Oxfam report landed in my inbox the same morning I was checking whether the energy bill would be reasonable. Billionaire wealth has hit £18.3 trillion globally. The number of billionaires now exceeds 3,000. Meanwhile, ordinary Britons are watching the meter and wondering whether to put the heating on.

I don’t know what to do with numbers like that. The human mind wasn’t built to comprehend trillions. We can picture a hundred pounds, maybe even ten thousand. But eighteen point three trillion? The figure floats free of meaning, disconnected from anything most can grasp.

What struck me wasn’t the figure itself but what Oxfam’s director said about it: “These billionaires are not content enough with being super rich. Now they’re buying political power... elections... media houses.” Wealth, it seems, is never just wealth. It wants more. It reaches for everything.

We don’t talk about money in church. We’ll discuss sex, suffering, doubt, death—but wealth makes everyone squirm. The rich feel judged; the poor feel invisible; those in between feel vaguely guilty without knowing why. So we stick to safer ground: personal piety, private devotion, the interior life. But I’ve been reading the prophets lately, and they won’t let me stay comfortable. They had rather a lot to say about who owns what, and what it does to us.

The Prophets Saw This Coming

Isaiah watched it happen in eighth-century Judah. Small farmers losing their land. Wealthy families buying up field after field. Villages emptying as ownership was consolidated. And he didn’t mince words:

“Ah, you who join house to house, who add field to field, until there is room for no one but you, and you are left to live alone in the midst of the land!” (Isaiah 5:8)

This isn’t abstract moralising. Isaiah describes a specific economic pattern: accumulation that displaces, wealth that grows by making others poor. The problem wasn’t that some people had large houses. The problem was that getting those houses required taking from others, until the wealthy “lived alone”—cut off from community, isolated in their abundance.

Amos raged against those who “lie on beds of ivory” and “lounge on their couches,” yet “are not grieved over the ruin of Joseph” (Amos 6:4, 6). Micah accused the powerful of coveting fields and seizing them, and houses, and taking them away (Micah 2:2). The prophets assumed private property. They honoured honest labour. What they couldn’t stomach was wealth that required someone else’s loss. Prosperity built on dispossession. Comfort that couldn’t see suffering at the gate.

When a single person’s wealth exceeds the GDP of nations, when three thousand people control more resources than billions combined, we’re watching Isaiah’s pattern on a scale he couldn’t have imagined.

Jesus Talked About Money Constantly

If you read the Gospels looking for economic teaching, you’ll find it everywhere. Roughly one verse in ten in Matthew, Mark, and Luke concerns money, possessions, or economic relationships. Jesus talked about wealth more than he talked about prayer. More than heaven. More than almost anything except the kingdom of God—and often the two subjects were the same conversation.

The rich young ruler came seeking eternal life. He’d kept the commandments. He was, by every measure, a good man. Jesus looked at him with love—Mark’s Gospel notes this specifically—and said:

“Go, sell what you own, and give the money to the poor, and you will have treasure in heaven; then come, follow me” (Mark 10:21).

The man went away grieving, “for he had many possessions.”

Read that again. Notice the grammar. The possessions had him. They’d become the thing he couldn’t release, the anchor holding him back from following where Jesus led. And then Jesus said something that shocked his disciples:

“It is easier for a camel to go through the eye of a needle than for someone who is rich to enter the kingdom of God” (Mark 10:25).

The disciples were “greatly astounded” because they assumed what most people still assume: wealth signals God’s blessing. If the rich can’t be saved, who can? Jesus didn’t soften the blow. He simply said that with God, all things are possible—implying that what wealth does to the human heart requires nothing less than divine intervention to undo.

Or consider the rich fool in Luke’s Gospel, whose land produced abundantly. His response? Build bigger barns. Store more grain. Take life easy.

“But God said to him, ‘You fool! This very night your life is being demanded of you. And the things you have prepared, whose will they be?’” (Luke 12:20).

The problem wasn’t the abundant harvest. It was that abundance became an end in itself, something to hoard rather than share, a source of false security rather than gratitude.

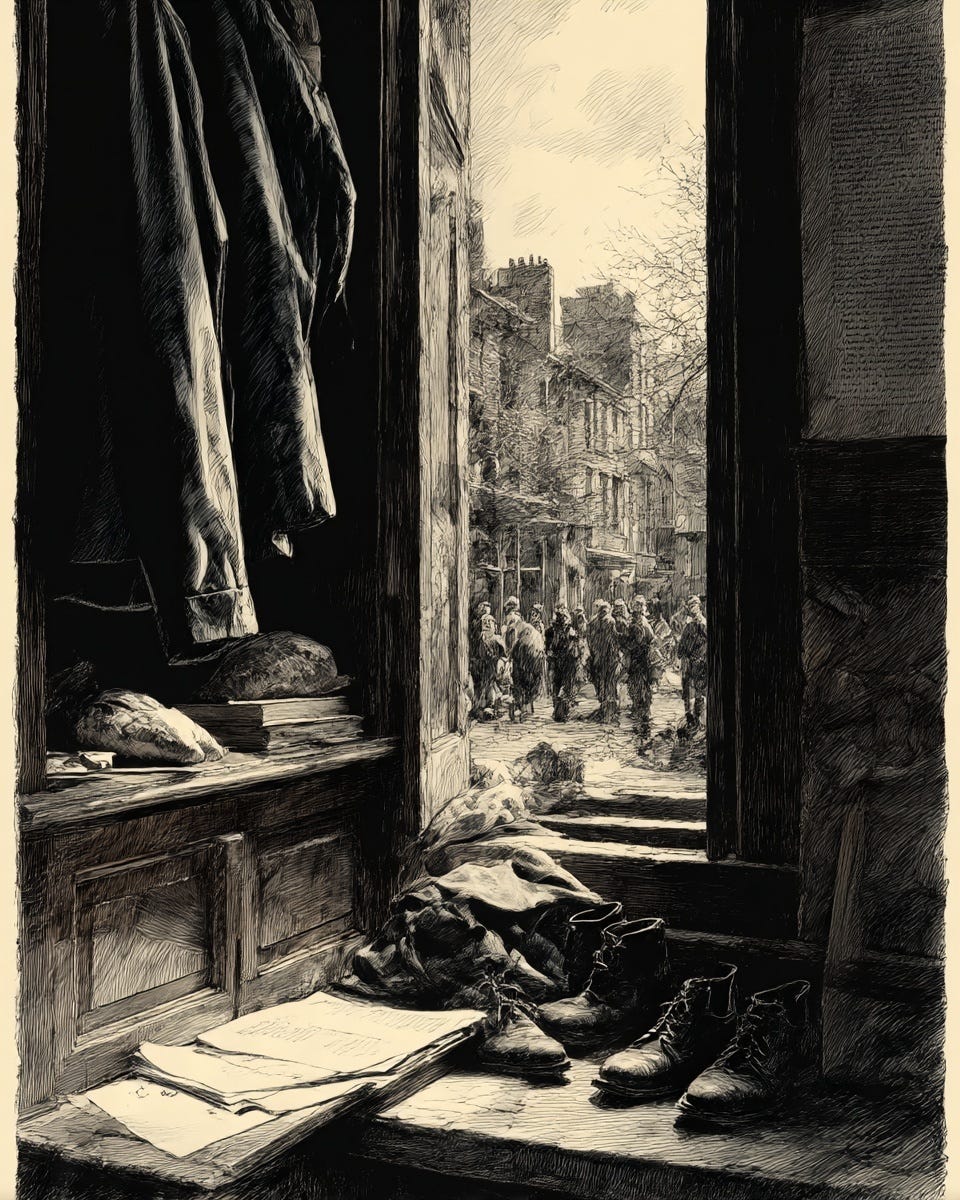

Then there’s Lazarus and the rich man—perhaps Jesus’s most disturbing parable. The rich man feasted sumptuously every day while Lazarus lay at his gate, covered in sores, longing for scraps. When both died, their positions reversed. But here’s what bothers me: Jesus never names the rich man’s specific sin. He doesn’t say the man cheated, stole, or exploited. The sin seems to be simply this: Lazarus was at his gate, and he didn’t see him. Abundance and destitution existed side by side, and the rich man remained untouched. The proximity of suffering didn’t penetrate his comfort.

The Early Church’s Dangerous Experiment

Something remarkable happened after Pentecost. Luke describes it twice, as if he couldn’t quite believe it himself:

“All who believed were together and had all things in common; they would sell their possessions and goods and distribute the proceeds to all, as any had need.” (Acts 2:44-45)

“Now the whole group of those who believed were of one heart and soul, and no one claimed private ownership of any possessions, but everything they owned was held in common... There was not a needy person among them.” (Acts 4:32, 34)

This wasn’t state ownership or government redistribution. It was something stranger and more personal: fellowship so deep that economic boundaries dissolved. The Greek word is koinonia—often translated “communion” or “sharing”—, and it meant holding life in common, not just beliefs. People, voluntarily and Spirit-led, held their possessions loosely. The community’s need became more compelling than individual accumulation.

The church fathers took this seriously. Basil the Great, preaching on the rich fool in the fourth century, didn’t mince words:

“The bread in your cupboard belongs to the hungry; the coat unused in your wardrobe belongs to the one who needs it; the shoes rotting in your closet belong to the one who has no shoes.”

Ambrose of Milan pushed further:

“You are not making a gift of what is yours to the poor man, but you are giving him back what is his.”

This reframes everything we call charity. It’s not generosity from our surplus. It’s returning what was never truly ours. The early church didn’t idealise poverty—they wanted no one to be poor. But they refused to accept that within the Christian community, the categories “rich” and “poor” should continue to exist. Where abundance and need existed side by side, something had gone wrong with their fellowship.

I think of the 172,000 children in Britain living in temporary accommodation. The number has more than tripled since 2010. These aren’t just statistics—they’re families displaced from stable housing, from schools and friendships, from the kind of rootedness the early church took for granted when it spoke of “not a needy person among them.” We’ve accepted systemic homelessness as normal. The early church would have found that acceptance incomprehensible.

What Then Shall We Do?

I wish I could end with a programme. Five steps to fix inequality. A policy platform baptised with Scripture verses. But that would be dishonest. The prophets didn’t offer policy papers. Jesus didn’t endorse tax rates. The early church’s experiment in radical sharing emerged from transformed hearts, not legislative mandate.

What I’m left with is something more uncomfortable: an invitation to see clearly, and to let that seeing change me.

But I’m also aware that individual seeing isn’t enough. The prophets didn’t just call out wealthy individuals—they indicted systems. When Isaiah denounced those who “decree iniquitous decrees” and “write oppression” (Isaiah 10:1), he named something we might call structural sin: arrangements that produce harm regardless of anyone’s intentions. The Oxfam report found that highly unequal societies are seven times more likely to see the rule of law erode. Concentrated wealth doesn’t just mean some have more—it changes the shape of society itself. When billionaires can buy elections and media outlets, when wealth translates directly into political power, the rules start bending towards those who already have the most. I don’t know what to do about that. But I know that pretending it’s only about personal virtue would be its own kind of blindness.

The numbers are so vast they paralyse. What can I do about £18.3 trillion? Probably nothing directly. But I can notice where my own life has been shaped by the same logic of accumulation—the assumption that more is always better, that security comes from storing up, that my abundance and another’s need can coexist without troubling my conscience. The rich man’s sin wasn’t his wealth. It was that Lazarus lay at his gate, and he didn’t see him. Seeing truly is itself a spiritual discipline. It’s where repentance begins.

I think about what “enough” might mean, too. The word has almost vanished from our vocabulary. Every advertisement, every financial plan, every cultural message assumes we should want more. But the rich fool built bigger barns precisely because he couldn’t recognise sufficiency when he had it. What if I tried to name a number—an amount that would actually be enough? The exercise itself feels countercultural, almost subversive. Which suggests how thoroughly the logic of accumulation has colonised my imagination.

The early church didn’t abolish private property. They relativised it. Everything they had was held loosely, available to the community's needs. I’m not sure what that looks like in a complex modern economy. But I suspect it starts smaller than systemic change—in the concrete generosity of actual communities, where people know each other’s needs and respond without shame or superiority. At its best, the church models an alternative economy. Not charity from above, but koinonia—fellowship so real that abundance flows towards need without calculation or condescension.

Isaiah’s warning echoes across the centuries. When wealth joins house to house and field to field without limit, eventually there’s room for no one else. The accumulators end up alone. The community fractures. The society corrodes. We’re watching this happen in real time, on a scale the prophets couldn’t have imagined.

I don’t know what to do about Davos. But I know the gate where Lazarus lies. It’s closer than Switzerland. And whether I see him—whether I let his presence disturb my comfort—is the question that will not leave me alone.

Questions for Fellow Pilgrims

When you hear statistics about billionaire wealth, what’s your gut reaction? What does that reaction reveal about your own relationship with money and security?

Jesus said it’s harder for the rich to enter the kingdom than for a camel to pass through a needle’s eye. The disciples were astounded because they assumed wealth signalled blessing. Do we still make that assumption?

The prophets weren’t against wealth but against wealth that insulates and dispossesses. Where do you see that pattern today?

What would “enough” actually look like for you? Have you ever tried to define it?

Going Deeper

Biblical and Patristic:

Craig Blomberg, Neither Poverty Nor Riches: A Biblical Theology of Possessions (1999)

Justo González, Faith and Wealth: A History of Early Christian Ideas on the Origin, Significance, and Use of Money (1990)

Basil the Great, On Social Justice (Popular Patristics Series)

Contemporary Theology:

Kathryn Tanner, Christianity and the New Spirit of Capitalism (2019)

William Cavanaugh, Being Consumed: Economics and Christian Desire (2008)

Pope Francis, Evangelii Gaudium (2013), paragraphs 52-75

Wow, the part about billionaires buying political power really stood out to me. You've articulated the issue of wealth accumulation so insightfully. What if this trend continues to accelerate, making our democratic institutions mere puppetts, controlled by those who can afford to pulll the strings? Such a truely chilling thought.